Shattered compositionality: how transformers learn arithmetic rules

I’ve had a recent paper with students where we made quite intriguing findings on transformers’ learning dynamics.

A lurking nightmare. Given the undisputed performance of recent LLMs such as GPT-5 and Claude Code, many of us have forgotten the early days of ChatGPT when it frequently made errors in basic arithmetic such as multiplication. Yet, the training recipe for pretraining, which is autoregressive training (aka next-token prediction) on transformers, stays largely the same. What has caused persistent defects in the current models will likely pass on to future successors. Of course, better training data and tool use have reduced hallucination for now, but who knows what awaits us when this technology is applied to many new domains on a large scale? A recent Nature paper on emergent misalignment shows the disconcerting risks.

A lingering puzzle of LLMs remains unsolved—

How do models build their own rules?

Here is a recurring question that has fueled endless debates since three years ago:

Are LLMs rule learners or pattern matching machines?

AI proponents contend that LLMs are capable of any knowledge work, while skeptics argue that LLMs are merely stochastic parrots that mix texts from training data. The gap between these two opposing narratives does not narrow if the lingering puzzle remains unsolved—how do these models figure out rules from data that differ from human’s expectation? While AI alignment develops practical techniques to address this mismatch, we have poor understanding about what causes the mismatch and how it emerges from autoregressive training.

Dissecting learning dynamics on synthetic experiments

Now that it has become impossible for most people to pretrain an LLM, we decided to train a small transformer from scratch on synthetic data. There are two big advantages of such synthetic experiments: first, we can track the model’s learning behavior using comprehensive evaluation metrics; second, we have full understanding and control over the training data. The synthetic experiments are not the end point of our study; instead they are means to a bigger end: understanding how learning dynamics induces a model’s peculiar behaviors. Of course, this doesn’t capture everything about real LLMs—but it lets us isolate one mechanism very cleanly.

One of the simple arithmetic tasks we studied in the paper is to solve a 4-operand addition. Our training data are text strings of the format $a + b + c + d = e$ where \(a,b,c,d\) are integers sampled uniformly from 0 to 999 and \(e\) is the correct result. Each string is a training example, tokenized character-by-character as one input sequence to the transformer. We adapted a simple training implementation to our setting. Since the model scale is very small, each complete run of the training cost little on Google Colab.

What do we expect from autoregressive training on our synthetic data? Let’s consider an example:

\[\begin{equation} (\text{plain format})~~~~~~349 + 102 + 382 + 907 = 1740. \end{equation}\]When a model is given the context (characters) preceding the first output digit 1, it needs to figure out the thousands-place digit by using all hundreds-place digits (namely 3, 1, 3, 9) before the equality, together with possible carry from lower digit places. Next, in order to correctly predict the hundreds-place digit 7 of the output digit, the model needs to compute a modulus-10 calculation together with possible carry from lower digit places. But this awkward calculation order is not what we learn in elementary school! It is much easier for start with units, the lowest digit place.

Let’s consider a human-friendly format where we reverse the order in the output integer.

\[\begin{equation} (\text{reverse format})~~~~~~349 + 102 + 382 + 907 = 0471. \end{equation}\]Now, the first digit in the output integer is 0, which is the modulus-10 result of \(9+2+2+7\). We don’t need to worry about carry as it is the unit place. Next, predicting the tens-place \(4\) requires calculating the modulus-10 result of \(4+0+8+0\) and carry from the unit place. By this point, we usually have kept our calculation for the unit place in our scratch paper, so it is easy to proceed with this order.

There are reasons to believe that the reverse format is easier to learn not only for humans but also for models, as advocated by this paper, because learning individual digits amounts to a composition of modulus-10 operations and carry in a linear progression.

The puzzle of reverse learning order

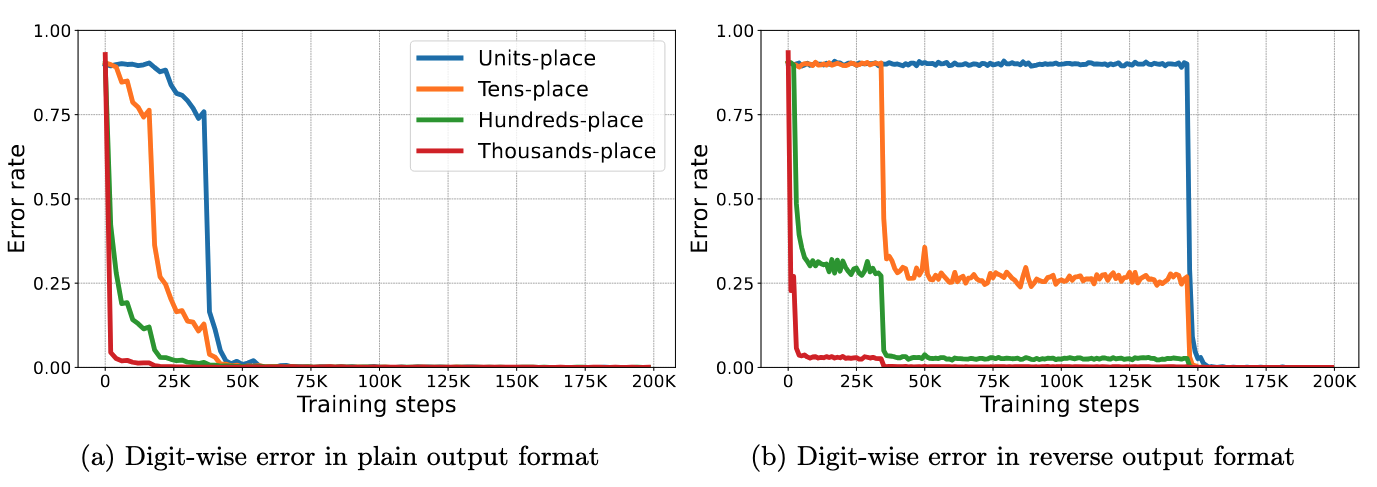

This expectation proves to be wrong. After running experiments separately with both output formats, we’ve found that transformers “insist” on learning from the thousands-place digit regardless of the output format!

The digit-wise error rates (comparing the model’s prediction with the correct answer) in the figure indicate that there is still a persistent linear learning order, but in the opposite direction to human’s rules. The setting with reverse output format that is supposed to be easier to learn, actually causes the model to learn slower: convergence takes much longer in the right plot, and the plateaus in the evolution of error rates suggest undesired loss landscapes.

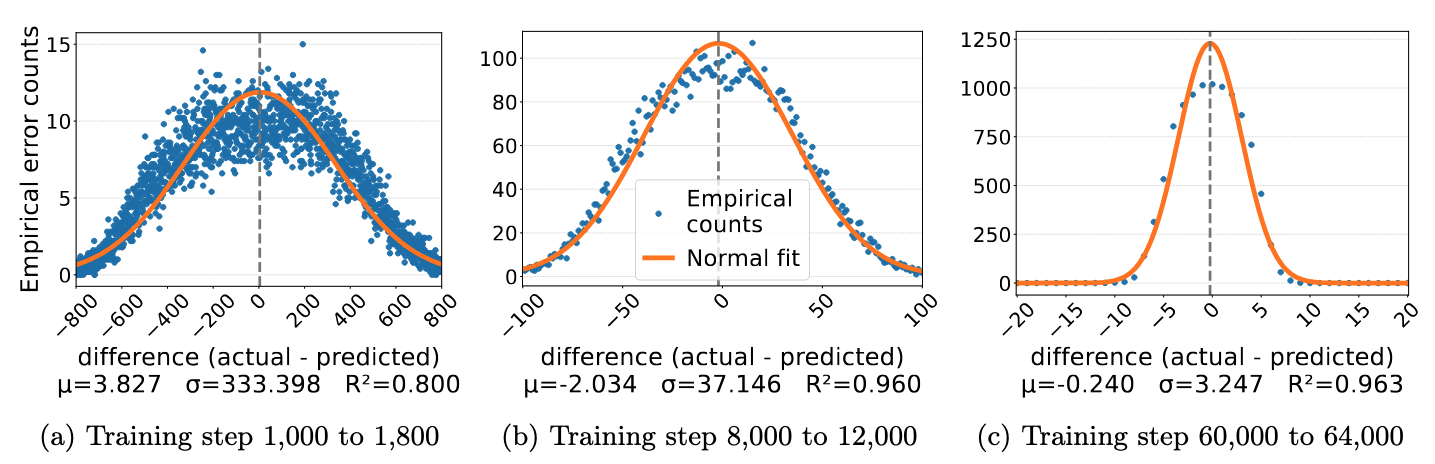

As we became baffled by this puzzle, an examination of the error distribution showed another striking phenemenon.

We computed the difference between the correct integer and the model’s predicted integer \(\hat{e} - e\) and treated this error as a whole instead of four separate digits. The figure shows that the errors are approximately Gaussian distributed, and the spread narrows as training proceeds. It tells us that the model behaves like an approximation algorithm—first figuring out the rough range of the output integer with a wide error distribution, then gradually refining the prediction with narrowing error distribution. Rather than learning the underlying algebraic rules of addition, the model appears to solve the task using an approximate, analytical strategy.

Can scaling fix this non-human learning order? We’ve tested the addition task with larger models and conducted a finetuning experiment using Pythia-1B. All experiments showed the consistent reverse learning order. We came to the conclusion that transformers are not rule learners, unless being fed with carefully designed reasoning data.

Correlational matching drives learning dynamics

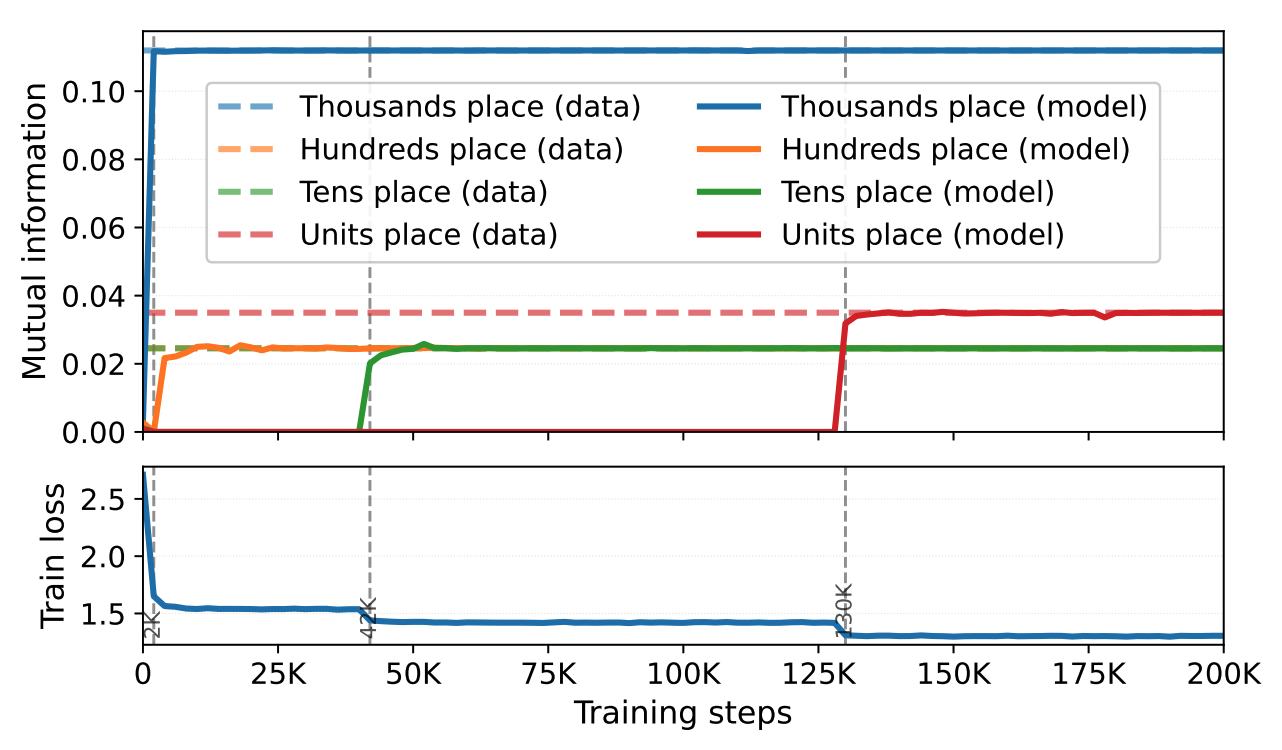

What is the cause of the counterintuitive learning dynamics? We turned to pattern matching as a plausible explanation. But a deeper understanding requires a definition of what we mean by the “pattern” or “signal” the model learns throughout training. I was motivated by the mutual information (MI) metrics in an earlier paper, so we considered the following metrics as a measurement of correlational structure from training data (recall that MI is zero if two random variables are independent). Let \(a=a_1a_2a_3\) be the digit representation of first input integer and \(e=e_0e_1e_2e_3\) be the output integer. According to our sampling of training data, all digits \(a_i\) and $e_j$$ can be viewed as random variables.

- Mutual information \(I(a_1; e_0)\): how much information the hundreds-place digit \(a_1\) provides for predicting the thousands-place digit \(e_0\)

- Conditional mutual information \(I(a_i; e_i \mid c_{i-1})\): how much information the input digit provides for predicting the output digit at the same digit place, conditional on the carry to the higher digit.

A positive MI means there is learnable signal in the training data, which can be captured by the (stochastic) gradient descent as we train a model. For example, a large \(a_1\) is more likely to yield a large \(e_0\), so this correlational structure offers a signal for the model to catch. Interestingly, \(I(a_i; e_i)\) itself is zero, whereas conditioning on the carry at a higher digit \(c_{i-1}\) yields positive MI \(I(a_i; e_i \mid c_{i-1})\). This provides a plausibility for the reverse learning order—a model starts with the signal in \(I(a_1; e_0)\) and proceed to lower digits since conditioning on acquired ``skills’’ at higher digits provides learnable signals.

We devised similar MI metrics to measure a model’s predictive behavior throughout training, and compared the evoluation of a model’s MI metrics against those calculated from the training data. The figure shows that critical drops in training loss match closely with phase transitions in the mutual information metrics. As we examined these plots, it became clear that correlational matching offers a much more convincing explanation for the model’s learning behavior—learning is driven less by discovering explicit rules and more by exploiting whatever statistical dependencies are easiest to capture early on.

Shattered compositionality causes brittle performance

For arithmetic tasks, pattern matching appears to be a winning narrative—but what are the consequences of this unexpected learning order? In our experiments, the errors eventually go down to approximately zero if we training long enough.

We continued our investigation into several other synthetic tasks and expanded to a few LLM experiments as well. We identified a few additional “warning messages”:

- Unpredictable learning behavior. Besides the reverse learning order, a transformer may learn arithmetic in multiple orders concurrently. This parallel learning mechanism often results in “skill competition”, where learning one pattern interferes negatively with learning another.

- Unintended mixing errors. A model generates unexpected mixing errors where a part of model’s output is repeated or swapped with another part.

- Deteriorating performance under distribution shift. Correlational matching soon becomes a liability when the test examples are from a different distribution. Even across many high-performing LLMs, slight twists of reasoning benchmarks yield much worse accuracy.

Once learning is driven by correlations rather than explicit rules, compositional structure becomes fragile, and failures begin to follow recognizable patterns.

Final thoughts

Our paper echoes some recent findings on compositionality in LLMs.

- Parallel mechanisms. In the Anthropic’s blog on the biology of an LLM, they discover the existence of multiple pathways within the model for solving complex tasks, some of which are in synergy and some of which are in competition.

- Bag of Heuristics. A recent paper that argues that LLMs solve compositional tasks with a bag of heuristics instead of using coherent rules.

To improve the robustness and transparency of LLMs, we need more evaluation metrics. Standard benchmarking is a good idea, but we can’t predict how LLMs may perform on out-of-distribution data or in a new domain. Our analysis of synthetic tasks is a first step toward building more robust and safer AI systems in the future.