Emergent unfaithfulness in chain-of-thought reasoning

My students and I have recently posted a paper, in which we aim to provide a fundamental understanding of chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning in LLMs.

So plainly intuitive and yet so perplexing. As one pillar of modern LLMs, CoT emerges as an effective strategy, both as a prompting technique and a training approach, for enhancing the reasoning capabilities. It’s hardly surprising that CoT works well for reasoning tasks, because this is what we are doing all the time when solving compositional tasks! Let’s say we want to evaluate a complex math expression. Realizing that it is difficult to find the solution directly, we grab a sheet of scratch paper and work through the intermediate calculations step by step. Assuming we have the patience, we could in principle work out a super long math expression if each step is simple enough.

But is step-by-step derivation “true reasoning”? What is really “true” or “faithful” reasoning?

LLMs can reason…unless it is for a show

Over the past three years, test-time scaling, namely increasing the length of the reasoning traces, has greatly improved the capabilities of LLMs. But the models are still prone to mistakes, such as producing incorrect reasoning steps or incorrect final answers, resulting in inconsistent reasoning traces. Such mistakes are not simply attributed to “noise” or “uncertainty” during generation; instead; they are inherent features tied to the training paradigm—the models are pretrained on long sequences of tokens to predict the next token as accurately as possible, without being explicitly told to follow logically consistent steps.

Post-hoc rationalization. LLMs sometimes “know” the solutions in advance of generating reasoning steps, yet still produce reasoning traces as post-hoc explanations (since they are trained to do so). This behavior is often referred to as implicit reasoning. More disturbingly, if a prompt contains “cues”—for instance, adding “a famous Stanford professor thinks the correct choice is C” before the question—which incentivize an incorrect answer, then models may “reason” to rationalize such an answer. The post-hoc rationalization behaviors exemplify the ambiguity of reasoning in current LLMs, which has far-reaching implications in AI safety.

A synthetic experiment for understanding CoT reasoning

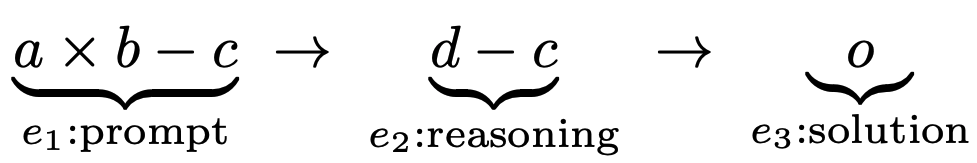

Let’s consider a simple synthetic experiment. We generate a random arithmetic expression containing two operators as the prompt, derive the intermediate simplification as the reasoning step, and the final correct number as the solution.

The numbers \(a,b,c\) are uniformly sampled from \(\{0,1,\ldots,N-1\}\) where \(N=97\). We treat the entire reasoning chain, including the prompt, reasoning, and solution, as one training example where we tokenize all numbers and operators. To keep our vocabulary size under control, the arithmetic is calculated under modulo \(N\); for example, if \(a = 23, b = 49\), then \(c = 60\) under mod 97. We also introduce corruption noise after a training example is generated: with probability \(\varepsilon_1 \ge 0\), the numbers in the prompt \(e_1\) are replaced by uniformly sampled numbers. Similarly, the reasoning step \(e_2\) is corrupted by independently sampled numbers with probability \(\varepsilon_2 \ge 0\).

Our synthetic data capture the step-by-step compositional structure of reasoning traces while stripping away natural language. If you know the standard math benchmark GSM8K, you may recognize this task as an idealized abstraction with a pure mathematical core. Training a small transformer model on these reasoning chains under standard autoregressive training, we want to understand how the model learns to predict both the reasoning step \(e_2\) and final solution \(e_3\).

Does training on reasoning traces produce causal reasoning?

What would we expect from this synthetic setting? It is hard to find an equivalent in the classical statistics or machine learning literature, because the targets of interest contain both the \(e_2\) and \(e_3\) with a compositional structure, as \(e_3\) is the result of composing two arithmetic steps.

Consistency in reasoning doesn’t imply a causal mechanism. In the noiseless regime \(\varepsilon_1 = \varepsilon_2 = 0\), a model observes only mathematically consistent reasoning chains and learns to do arithmetic operations. However, we can’t tell a priori how a model learns to predict \(e_3\)—in theory it may depend entirely on \(e_1\) by ignoring \(e_2\), or conversely entirely on \(e_2\) by ignoring \(e_1\), or on both \(e_1, e_2\), all of which would result in the perfect accuracy. So it becomes clear that we can’t understand the role of the reasoning step by checking consistency alone.

To evaluate the causal effects of the reasoning step, we need to do more: by intervening on \(e_2\) such as perturbing the numbers, we can measure how much \(e_3\) is altered, an approach used by the prior work. We will then understand how much a model’s prediction of \(e_3\) causally depends on \(e_2\), which helps us to differentiate faithful reasoning from unfaithful post-hoc explanations.

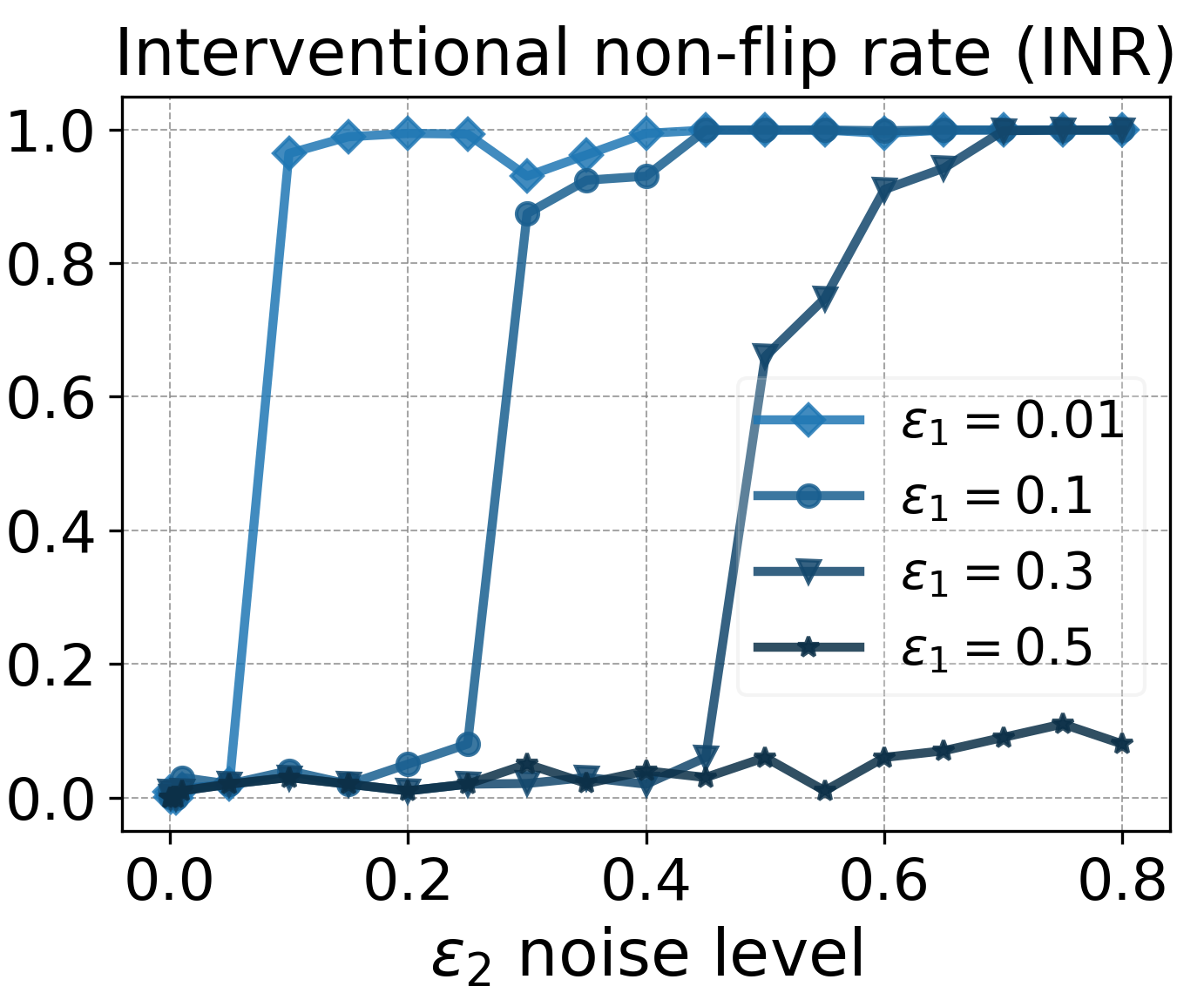

In our experiments, we trained transformers under different settings of noise levels \(\varepsilon_1, \varepsilon_2\). Then, we evaluated each model at the final checkpoint using an intervention-based metric that we call Interventional Non-flip Rate (INR). A small INR means that intervention on \(e_2\) flips \(e_3\) more frequently, thus the causal effect of \(e_2\) is stronger.

The above plot shows that there are critical noise thresholds governing the causal faithfulness of models’ reasoning behaviors.

- For the noiseless setting, a model’s CoT reasoning is highly faithful.

- Faithful reasoning behaviors persist even in settings where \(\varepsilon_2\) is slightly larger than \(\varepsilon_1\).

Why is causally faithful reasoning possible? Learning skip-step reasoning would yield zero training loss as well. This is an example of algorithmic effects, usually known as Occam’s razor or the inductive bias of gradient-descent-type algorithms. In the paper, we conducted further analysis to confirm the model’s tendency to learn a simpler mapping in the presence of competing mappings.

Pattern matching vs. causal reasoning. An enchenched debate about LLMs is whether they are pattern matching machines (aka stochastic parrots) or causal reasoners. I’ve also touched this topic in my previous blog post on shattered compositionality. Our findings here suggest a hypothesis that reconciles the two opposing views:

While I haven’t tested this hypothesis beyond our synthetic experiments, it does explain a common belief that the reasoning abilities of LLMs are very much powered by high-quality training data.

Model learns to check if reasoning trace is inconsistent

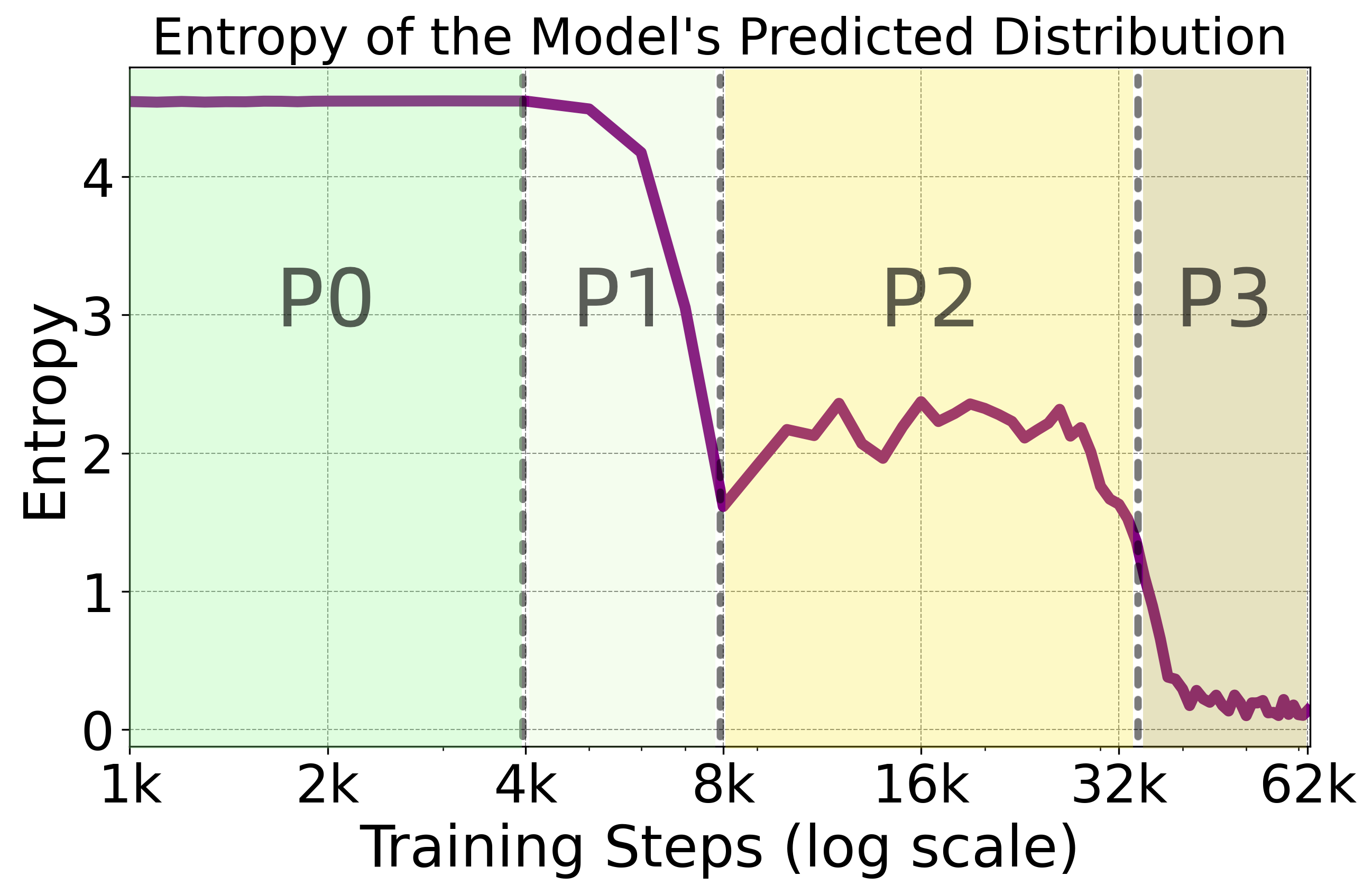

As we increase the noise level, how does unfaithfulness emerge from the training dynamics? If the prompt \(e_1\) and the reasoning \(e_2\) are inconsistent, how does a model predict the solution \(e_3\)? To answer these questions, we evaluate the models across the entire training dynamics. In particular, we measure a model’s uncertainty by calculating the prediction entropy of prediction at the solution token. A high entropy indicates high uncertainty.

We find that there are distinct phase changes of reasoning modes across training: a model transitions from step-by-step faithful reasoning (P1) to mixed reasoning (P2) and eventually to unfaithful reasoning (P3). The model’s solution mostly depends on \(e_2\) in P1 and on \(e_1\) in P2. Interestingly, the above entropy plot shows that the model learns to develop internal uncertainty in the mixed reasoning phase, as it needs to resolve inconsistency between \(e_1\) and \(e_2\). This emergent phenomenon is indicative of self-verification behaviors widely observed in LLMs: they are able to reflect on and verify their own reasoning traces even before any dedicated reasoning training.

Bigger puzzle remains: emergence of meta-learning skills

Let me put down some final thoughts about reasoning models. Reasoning is universally perceived to be one core component of intelligence, yet as LLMs cruise through harder and harder math/coding benchmarks, we have little understanding about its emergence. Last year, the “Aha moment” in the DeepSeek-R1 paper generated as much confusion as excitement, which is a testimony to the embarassing fact that we created a form of intelligence that we know little about.

Looking ahead, much work is needed to resolve the puzzle.

- How can we define causal or faithful reasoning in general?

- How does complex self-reflection behavior emerge in LLMs?

- How does RL training enhance a model’s reasoning capabilities? And what are the limits?

These are exciting questions to pursue. Writing at the start of 2026 when LLMs continue to rapidly evolve, I look forward to the predictable unpredictability of this field in the year ahead.